2025 Nobel Economics Prize : our analysis

Has a Focus on Economic Growth Limited Perceptions on Development? A Discussion of the 2025 Nobel Prize Winners.

This week, the Swedish Royal Academy announced the winners of the Nobel Prize for Economics. The recognition was shared between Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, who focused on the relationship between innovation and economic growth.

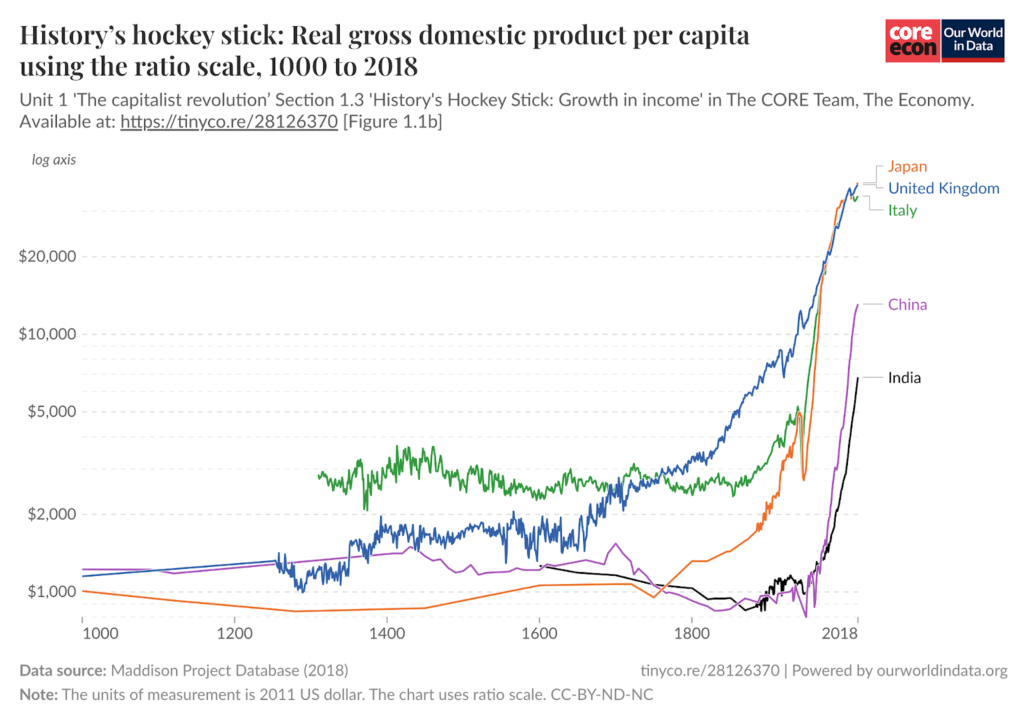

However, the Nobel Prize in Economics is often scrutinised. Not only does it tend to favour Western-focused institutions and research, but it also usually awards ideas that stay within the scope of neoclassical economics. Among them, the question of sustained growth has become increasingly relevant in the field, given its presence exclusively in the last 200 years of human history (Our World in Data, 2018).

In a global scenario characterised by income inequality, the climate crisis, and fragmented political landscapes, it is common to question whether these highly celebrated economic models offer pragmatic answers, and especially to what extent they are relevant for emerging economies. Is economic growth through innovation still the key issue policy should address? Or has it taken the spotlight away from other key issues within development, shaping a limited economic policy discourse?

Innovation, Competition & Growth – An Insight into the Laurettes’ Work

Joel Mokyr, an economic historian, focused his research on identifying the conditions under which growth can be sustained through technological progress. Observing Great Britain during the Industrial Revolution, the author sought to explain the unprecedented and sustained economic growth. Mokyr illustrates that the main difference is that, after the Industrial Revolution, societies began valuing an understanding of why things work, rather than just how, thus allowing for continued innovation by building upon existing knowledge.

Along similar lines, Aghion and Howitt developed an economic model demonstrating how growth is a consequence of ‘creative destruction.’ In other words, firms that introduce innovation in the market will outperform those that do not, thus eliminating obsolete products by replacing them with improved ones. The model also considers using patents to generate economic profits, which serve as incentives for continued investment in innovation. Consequently, the authors emphasise the importance of policies that encourage and protect innovation to sustain long-term growth.

The work of these Nobel Laureates is only a portion of the research focused on fostering growth through technological innovation. These arguments have a significant implication for policy development and analysis, where governments may design their budgets around these aims. For instance, Aghion and Howitt’s model can help determine how to subsidise industries to maximise social welfare (SOURCE).

Has A Focus on Growth Led to a Limited Perspective on Development?

If we assume that the aim of achieving growth is to improve people’s livelihoods worldwide, and that the way to do so is through technological progress. In that case, we can identify some limitations to this approach. Economic wins might not lead to the desired outcome if the methods to get there neglect key limitations. If we consider the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, economic growth is only one of the objectives.

In the wake of the climate crisis, ignoring the negative externalities of technology, especially on the environment, would be a critical mistake. The growing need for natural resources to develop or maintain these innovations can lead to pollution and unsustainable extraction practices (Mohan, 2025). Moreover, the context under which these resources are exploited tends to be characterised by conditions that violate human rights. These externalities carry greater weight when considering the unequal distribution of labour, and thus of the burden, between the Global North and the Global South.

A key example of this is the cobalt industry in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where ‘freelance’ workers are exposed to dangerous labour for only a few dollars a day (Gross, 2023). Similarly, South American communities are now experiencing a ‘white gold rush,’ as the increase in demand for lithium presents them with opportunities to exploit it. The lack of stable institutions, undirected policy, and unsustainable mining practices could bind the region to the ‘resource curse,’ where countries rich in natural resources often exhibit high levels of poverty and inequality (Singh, 2024). Both minerals are key to developing new technologies, especially innovations aimed at replacing fossil fuels. While innovation can lead to economic growth through the development of new goods and the exploitation of resources, irresponsible sourcing to meet growing demand can have negative consequences for social and environmental well-being.

Moreover, these divisions of burdens between the Global North and South could also imply an unequal distribution of economic rents due to innovation. Therefore, while innovation can still be beneficial, the gains might be skewed. Consequently, inequality is not only affected between countries, but also within them. A working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggests that firms concentrate a large portion of the surplus in new patents, and that the benefits are concentrated among higher-earning workers and investors (Kline et al. 2018). Therefore, while economic growth is achieved through innovations, the profits may not trickle down evenly to the rest of society. Similarly, a working paper by UCL emphasises the role of modern institutions in making rent concentrations more persistent (Mazzucato et al. 2020). In this way, the question of achieving growth through innovation is insufficient if policy designs overlook the possibility of an unequal distribution of benefits, which can contribute to increased income inequality.

Finally, this last point underscores the role of institutions in facilitating innovation and, consequently, growth. Mokyr’s focus on a society’s openness to change might neglect the relationship between the evolution of institutions and culture (Hodgson, 2021). Echoing the work of last year’s Nobel winners, innovation can be highly related to the nature of institutions; do they distribute knowledge, resources and power equally to foster innovation? (Acemoğlu & Robinson, 2012). Hence, it is also necessary to account for the structural reality of economies in pursuing growth and consider the historical legacy that led to their emergence in the first place (for example, colonisation).

Conclusion: False Dichotomies in Economic Thought & Policy-Making

Completely discrediting economic growth as a relevant aspect of development could also be detrimental. Higher levels of GDP, a measure of economic development, are strongly correlated with better standards of living and a higher quality of life.

However, studying innovation-led growth in isolation can be as inefficient as not doing so at all. Critiquing growth-centred approaches to development can highlight relevant limitations in our approach to the field. Taking into account the role of externalities, inequality, institutions, and structural legacies is key to developing policy that chooses to tackle economic growth, equality, and a secure standard of living.

Overall, economic policy and theories should be approached with nuance and should not be treated as isolated ideas. This year’s Nobel Prize is just a piece of a larger puzzle in the effort to achieve sustainable development and global equality. Growth can be positive and limited in scope and impact. Most importantly, one-size-fits-all approaches should continue to be questioned, even if highly esteemed in the field. Complementary theories and models can contribute to addressing these limitations, particularly those that centre the overlooked perspectives, experiences and contexts of the Global South.

Instead of asking whether we should focus policy on a particular aspect of development over another, it may be time to start evaluating how they are all interconnected. Can we design holistic policy to ensure growth and well-being in the Global South if our research remains focused on the Global North as a benchmark?

References:

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. “Culture and Institutions: A Review of Joel Mokyr’s A Culture of Growth.” Journal of Institutional Economics 18.1 (2022): 159–168. Web.

Kara, Siddharth. “Red Cobalt in Congo’s DRC Mining.” NPR, 1 Feb. 2023, www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2023/02/01/1152893248/red-cobalt-congo-drc-mining-siddharth-kara.

Mazzucato, M., Ryan-Collins, J. and Gouzoulis, G. (2020). Theorising and Mapping Modern Economic Rents. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2020-13).

Mohan, Deepanshu. “Nobel Award: Celebrate Creative Destruction but Spare a Thought for Its Impact beyond GDP Growth.” Mint, 17 Oct. 2025, 01:00 pm IST, www.livemint.com/opinion/online-views/nobel-prize-2025-economics-joel-mokyr-philippe-aghion-peter-howitt-creative-destruction-industrial-policy-india-factory-11760676068822.html.

Patrick Kline, Neviana Petkova, Heidi Williams, and Owen Zidar, “Who Profits from Patents? Rent-Sharing at Innovative Firms,” NBER Working Paper 25245 (2018), https://doi.org/10.3386/w25245.

Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, “A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction,” NBER Working Paper 3223 (1990), https://doi.org/10.3386/w3223.

Prize in Economic Sciences 2025 – Popular Information.” NobelPrize.org, The Nobel Foundation, 2025, www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2025/popular-information/.

Singh, Jewellord Nem. “How Latin America Can Harness the White Gold Rush.” The World Today, Feb. 2024, Chatham House, 2 Feb. 2024, updated 21 Mar. 2024, www.chathamhouse.org/publications/the-world-today/2024-02/how-latin-america-can-harness-white-gold-rush

Unit 1 ‘The capitalist revolution’ Section 1.3 ‘History’s Hockey Stick: Growth in income’ in The CORE Team, The Economy. Available at: https://tinyco.re/28126370 [Figure 1.1b]

Leave a Reply